Why people do what they do

Understanding human behaviours and social phenomena

Introduction

Consider a community with near-universal open defecation rates. The issue is not a lack of toilets–after researching locations, many were recently built and placed in high-traffic areas. Men, women and children pass these well-lit, centrally-located toilets on their way to work and school, and en route to fetch water. Many would rather walk 35 minutes to a well-known, isolated open defecation location to relieve themselves.

This daily decision, made by a vast majority of community members for generations, has contributed to countless deaths from diarrhoea, cholera, intestinal worms, trachoma and many other diseases. This decision also increases the risk of sexual assault for women travelling to these isolated sites. In the following section we'll explore how an SBC approach can help us uncover some of the hidden drivers of this behaviour, enabling us to support and stimulate positive change.

Studies estimate that people make over 35,000 decisions a day. Each individual decision has ripple effects on others, from loved ones – children, spouses, family members, friends – to community members – neighbours, teachers, friends and peers – to society at large. Environmental, social and political dynamics influence the decisions we make and these dynamics are influenced by those decisions. By understanding what informs individual and collective decision-making, we can support people to make healthy, positive choices for themselves and for broader society. When we understand the drivers of behaviour, we can support policymakers and development practitioners to design strategies that enable positive decision-making.

Why SBC?

Let’s return to our open defecation challenge. Social and behavioural analyses would reveal that for this community, the practice of open-defecation is a habit carried out over generations. Habits are hard to break, especially when attached to long-held cultural norms. Before toilets were available, the practice of travelling to an open defecation site was paired with the task of fetching water. It was not only convenient to combine tasks, but it also offered a chance for neighbours, friends and family members to spend time together. Traditional beliefs also considered this a healthy choice– walking before relieving oneself was positively perceived. As such, successive generations were raised thinking that this was the right thing to do. Building toilets alone could never disrupt a social tradition built over generations. Open defecation was never going to be solved with toilets alone. It was an individual behavioural challenge supported by generations of community practice and social norms.

Social and Behavioural Science is the study of human behaviour– the investigation of why people– both as individuals and as part of groups– perceive, think and act in particular ways. It seeks to explain some of the seemingly strange and irrational things we do, while generating ideas to help people make more positive choices. It underpins each one of UNICEF’s strategic priorities. Children are affected by the 35,000 daily decisions of the adults who shape their lives. Mastering the science of human behaviour is essential to supporting environments where children can thrive.

UNICEF’s models to understand social and behavioural change

People are diverse and unpredictable. How can we better understand them and even predict what they’ll do?

While we are all different, a growing body of research is revealing there are consistencies in human decision-making and behaviour. This research has challenged classical, 'rational' models of behaviour used in economics. Social, historical and cultural contexts, the environment and how mental shortcuts shape everyday decision-making are increasingly informing work in this space. Behavioural Science employs evidence and data from people all over the world to design theories that explain – and ideally predict – how and why people make decisions.

Behavioural theories and models can provide an evidence-based framework, to analyse, design and evaluate work in SBC.

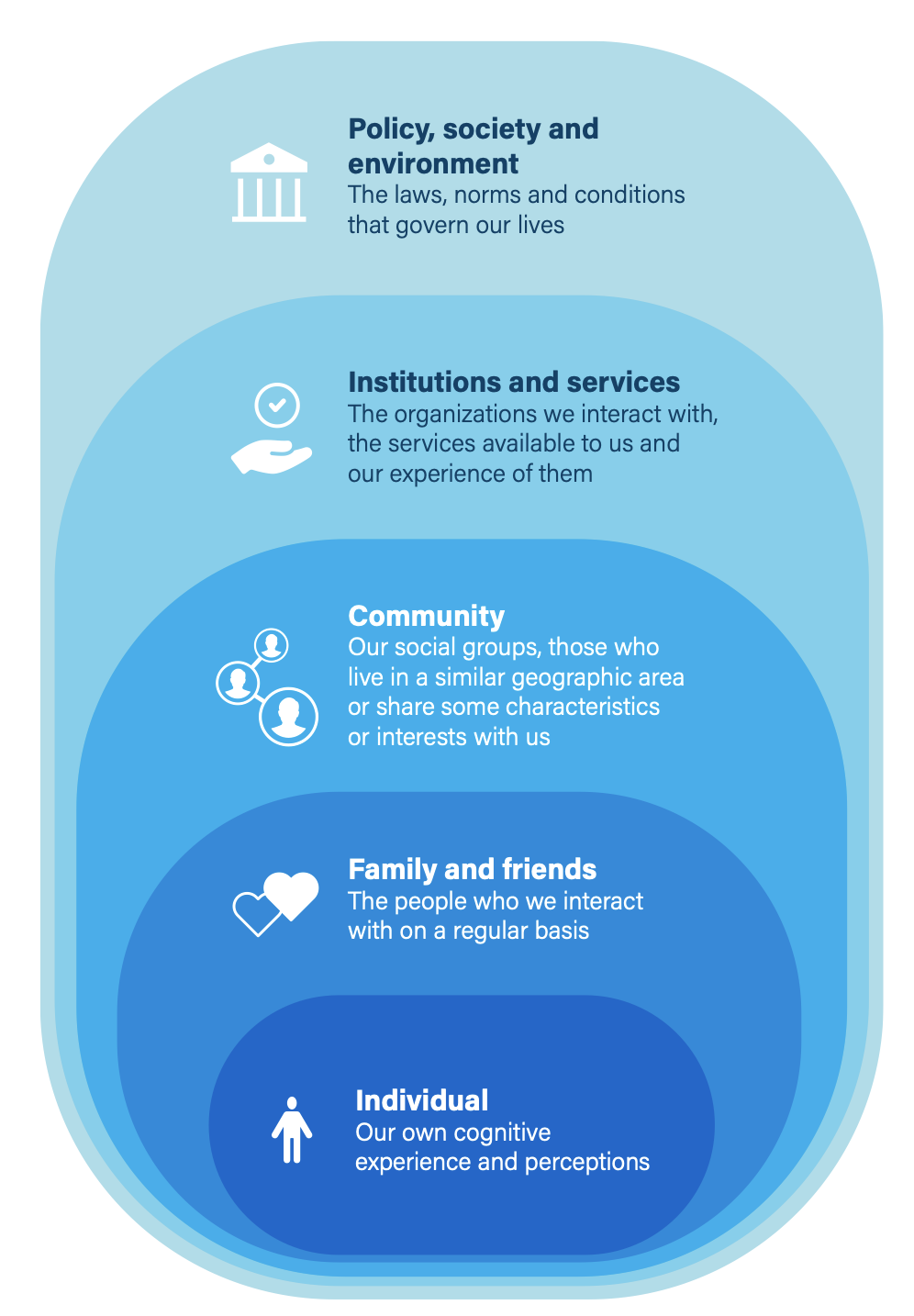

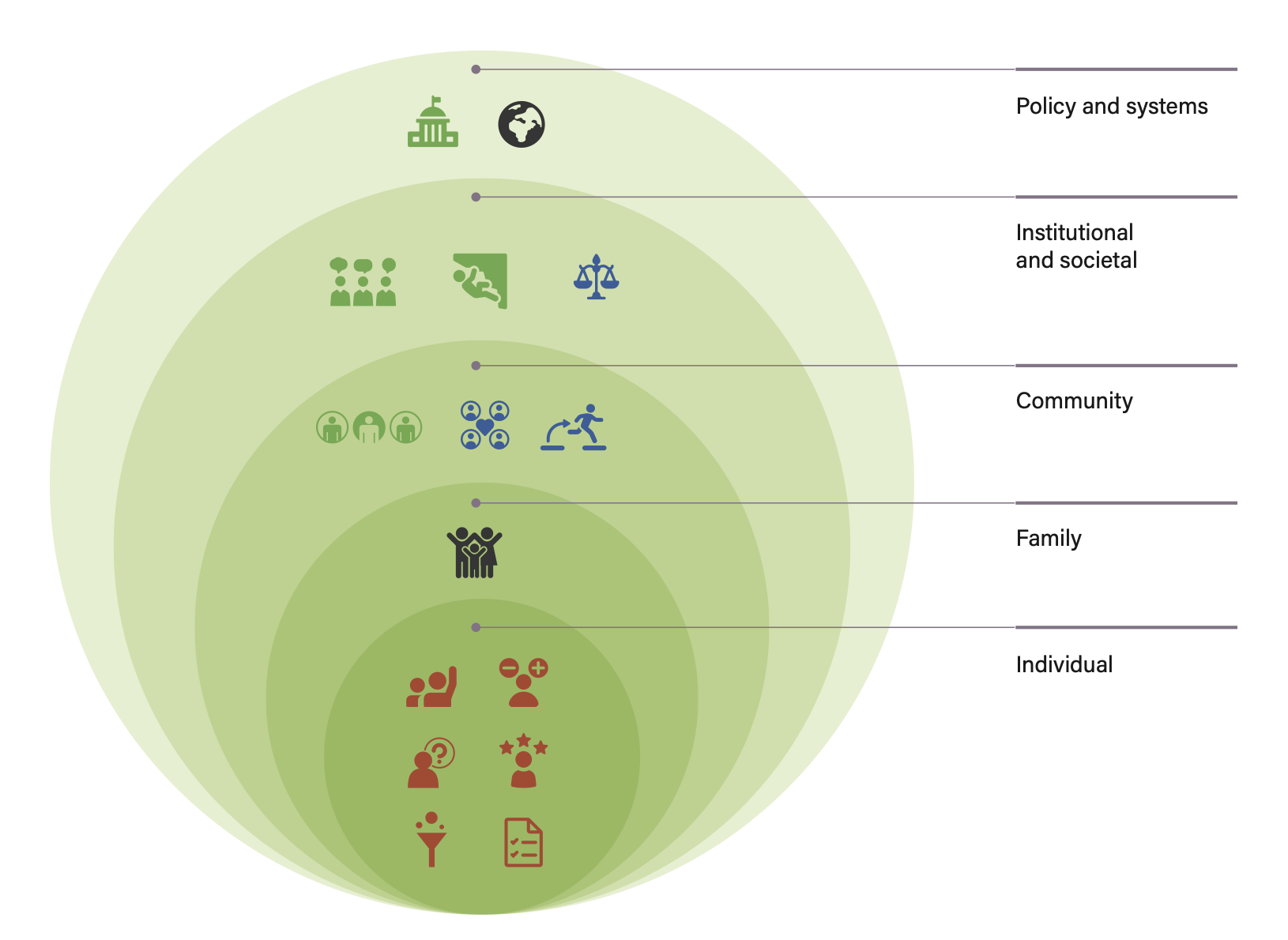

The Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) is UNICEF’s foundational model for social and behaviour change. It highlights the factors that influence both individual and collective human behaviour. These factors are:

- Policy, society and environment: the laws, norms and conditions that govern our lives

- Institutions and services: the organizations we interact with, the services available to us and our experience of them

- Community: our social groups, those who live in a similar geographic area or share some characteristics or interests with us

- Family and friends: the people who we interact with on a regular basis

- Individual: our own cognitive experience and perceptions

The SEM provides an individual, social and systemic lens through which to ensure that all research, strategies and programmes account for these key levels of influence.

Behavioural drivers model (BDM)

While the SEM outlines the broader structures that influence behaviour change, it doesn’t articulate the specific dynamics at each level. The model does not include the cognitive and social mechanisms that influence us and the specific theories that can be used to drive change. However, there are a number of behavioural models that do. One study identifies over 82 models of behaviour change, focusing solely on the individual. Other behavioural models and theories unpack community-level dynamics, examining the role of social norms and social networks. Behavioural Economics offers various models, heuristics and biases to explain psychological and environmental levers of change. Sectoral disciplines like Healthcare draw on models of risk and cost benefit.

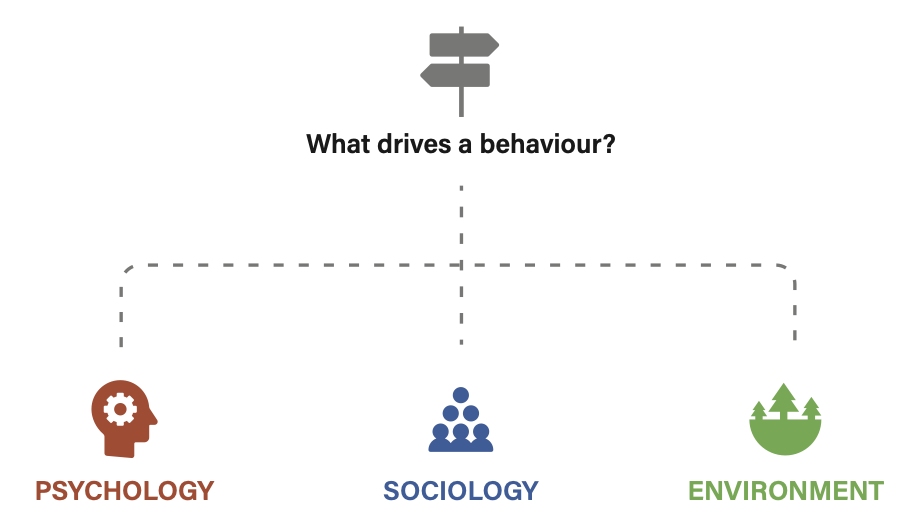

The Behavioural Drivers Model aggregates many of these different models to group three important levers of change:

- Psychological

- Social

- Environmental

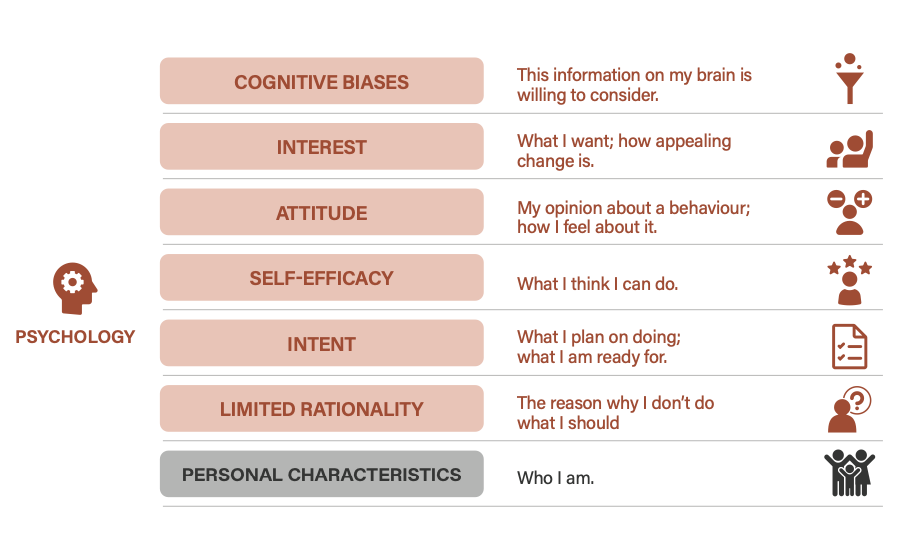

Psychological: this category examines the demographic and social characteristics that make people unique. This includes the beliefs, intentions, perceptions and biases that influence decision-making.

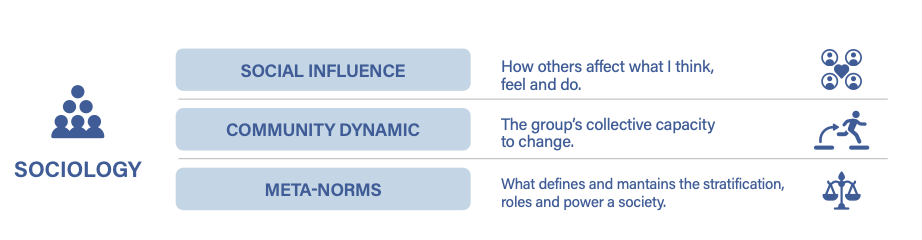

Social: this category explores the notion that people are never fully autonomous, by unpacking the effects of social influence and norms. People are heavily influenced by and concerned about the opinions and actions of others. Positive and negative social norms can play a huge role in personal decision-making.

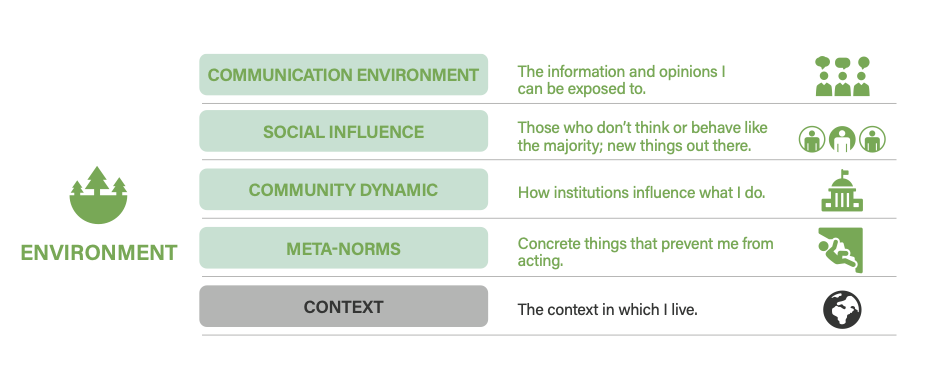

Environmental: this category unpacks the wide range of influences that exist in the space around us. What people hear in public and private discourse can reinforce or challenge what they think. New and emerging viewpoints can be catalysts for alternative ideas. Governments, policies and services can also encourage or discourage certain choices. . All of these elements make up the context in which people live and form behaviours.

It is important to emphasize that the Behavioural Drivers Model and its components are ecological in nature. The factors depicted in the BDM can be spread across the various levels of the SEM.

Understanding human behaviour

Behavioural models like the SEM and the BDM explained above are helpful tools for structuring your research. They can help you identify missing gaps in your data landscape, organize your behavioural analysis and pinpoint where investments can have the most impact.

While there are hundreds of models to choose from, many have been generalized to apply to most topics and challenges (for example, the COM-B model mentioned below). Because of this, models need to be adapted to suit your situation. With whatever model you choose for the challenge you face it is vital to test it with real evidence from your context to adjust your assumptions. By doing so, you can ensure the strongest outcome for your unique scenario.

Human behaviour is complicated. To effectively address behavioural challenges, you need to combine tools and insights from an array of disciplines. Collaborating with people and communities throughout the change process is one of many core principles that are critical to ensuring that SBC is as effective as possible.

Below is a list of disciplines you can draw upon to help you understand – and solve – complex behavioural challenges. This list is not exhaustive and should be expanded to suit your need and the evolving nature of the discipline.

Discipline | What it can bring to SBC | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

Psychology | An understanding of the mind and our mental and cognitive processes (referred to as individual drivers of behaviours above). | May not consider the broader environmental or social context. |

Social Psychology | An understanding of how human cognitive processes, decisions and behaviour are influenced by social interactions. | Specific to local context. |

Anthropology | An approach to research from the perspective of someone within the social group, also known as emic research (its compliment, etic research, considers the perspective of the observer). This approach focuses on holistic life experience, offering social, cultural, and linguistic insights.

| Can be time consuming and researchers bring their own particular viewpoints and interpretations. |

Sociology | A way to analyse human societies, including social groups, social relations, social organizations and institutions. Although sociologists' study what are commonly regarded as social problems such as violence, drug addiction and poverty, they also examine fundamental social processes present in any society: social hierarchy, social networks, social change, conflicts and inequality. | Deals with phenomena which are observed but often cannot be tested through experimentation. |

Political Science | An understanding of institutions, policies, practices and relations that govern public life. Political science can also bring important insights about power: how it is acquired and retained in society, and how it can achieve or erode equity and trust. | Focuses primarily on structures, not necessarily people. It can sometimes be overly theoretical unless combined with contemporary history, political analysis and real-world application of policies. |

Communications | Key insights into the patterns of interpersonal relationships and how people interact. It also explains the existence, use and effects of different forms of communications (including media) in different social and cultural contexts. | Often mistaken as a tactic to influence people rather than as a field of science. |

Behavioural Economics | Theories that shed light on actual human behaviour, which has been proven to be less rational, consistent and selfish than what traditional normative theory suggests. It places a large emphasis on shifting behaviour through structural and contextual changes, as well as small changes that target psychological levers. | The field is undergoing a replication crisis. Many of the experiments that lay the foundation for its theories have recently been called into question for either failing to replicate or for being overly-reliant on samples from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) countries. This panel discussion from the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team can provide further context. |

Public Health | A unique tradition of frameworks and models to SBC that can be adapted to other sectors: frameworks like the Health Belief Model and COM-B that explain risk and risk perception, cost-benefit calculations, severity and susceptibility, motivation, etc. Public health brings an important approach to all technical areas that UNICEF works within (Education, WASH, Child Protection, Social Policy, Health and Nutrition, etc.) that each have their own body of knowledge. | The Health Belief Model (HBM), one of the foundational and most commonly cited models in Public Health, is critiqued for being overly simplistic and theoretical, as it assumes people make calculated, rational decisions based on facts presented to them. Behavioural Economics theories can complement the HBM to better integrate and predict real-world behaviour. |

Gender Studies | An understanding of gender as a significant factor in familial, social, and economic roles. It helps us identify gender-specific norms and power imbalances that affect decision-making. It also helps us understand the ways gender intersects with other identity markers such as ethnicity, sexuality and class. | Using scientific insights about gender might require careful framing to avoid being dismissed or challenged in conservative and patriarchal contexts. |

Understand - Why people do what they do

Download this article as a PDF

You can download the entire page as a PDF here