Diagnosing the Situation

How to make sense of your data

Introduction

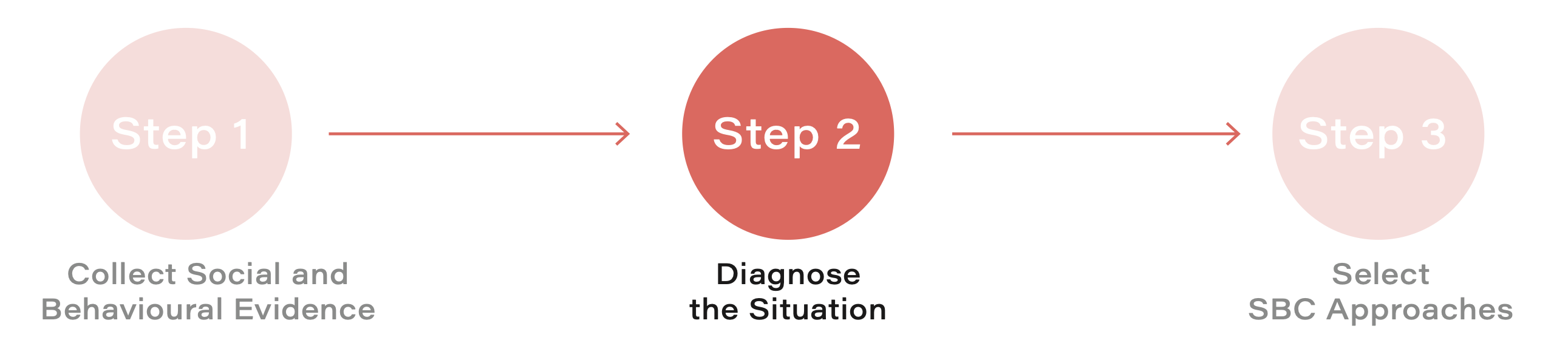

Once you have collected your Social and Behavioural Evidence, you are ready to start diagnosing the situation.

This process will help you ground all challenges and decision-making in relevant evidence and local insights.

What is diagnosis?

The process of thoroughly analysing data, information and research to develop an in-depth understanding of a situation.

By finding clarity in the noise, you can uncover the root cause(s) of the challenges at hand, existing local strengths and initiatives, and viable solutions to help overcome challenges. Taking time to sift through the evidence and diagnose the situation will help you determine which psychological, social or environmental elements can be leveraged. This enables you to design a resulting strategy that truly involves and serves the affected population.

Why is diagnosis important?

UNICEF’s work is focused on addressing development and humanitarian challenges that affect communities and families. Every community has its own unique context, history and social dynamics that affect the way they engage with programmes and institutions like ours. Understanding this history and developing a deep understanding of the specific context and needs will help ensure that programmes are impactful and resources are allocated efficiently. However, making meaningful connections between the different pieces of data you have collected requires a significant time investment.

Objective

You have successfully diagnosed the situation if you can create Problem and Opportunity Statements.

A Problem Statement is a concise framing of the main challenge. It is very likely that the research will present more than one challenge. However, focusing on one pressing issue will almost always prove to be more effective. An Opportunity Statement is a concise framing of how local strengths, wisdom or positive norms can be leveraged to overcome the main challenge. Early on in your research, you may uncover viable solutions that already exist locally or in similar contexts, as well as material and immaterial community assets that could be key moving forward.

A good statement frames the challenge or opportunity from the perspective of affected community members, or acknowledges how it directly affects or relates to them. These statements will help you develop a human-centred strategy.

Management tip: You may be working with an external consultancy or service provider to help you diagnose the problem. To set expectations and ensure that deliverables suit your objectives, it is good to be familiar with the process. For example, it may be effective to map research insights to a particular behavioural or social model (see Organizing/Mapping below). You may want to make this step required within the contract deliverables. |

Key tips for success

- Don’t delay your analysis

Once the evidence has been collected, you should begin analysis right away. Transcribe interviews immediately so that details like tone and emphases are not forgotten. - Make sure you have enough time

Sometimes insights are not immediately obvious and may require deep thinking to connect the dots. At a minimum, you should set aside three days for analysis for each day of data collection in the field. This is known as the 3x rule. While quantitative data may take a little less time to analyse than qualitative data, use the 3x rule to ensure you have spent adequate time on analysis. Take time to triangulate your data, to double-check that everything ‘feels right’. - Don’t do it all by yourself

Diagnosis can be very tiring, which may result in overlooking key insights in the data. Furthermore, different perspectives and experiences can influence the way we see things. To ensure that all data are properly considered, you should work with a mix of minds from various disciplines and invite outside teams to help. Working with a diverse team helps combat biases that affect how we interpret information. When working together, create space for both individual and group input. - Get creative

Don’t spend too much time staring at a screen. Working offline can help you see the same information from new angles. You could print out interview transcripts so that you can scribble notes and ideas in the margins. You could make a rough sketch of an experience shared in the data. You could even take a walk when you re-listen to an interview. Our minds work differently when working on a screen, so it’s important to find creative alternatives so that you have space to think clearly about the evidence collected. - Triangulate with other data and knowledge

Before conducting primary research, you should carry out a desk review to identify evidence that already exists in the focus area (see the Collecting Social and Behavioural Evidence tool). Having this knowledge base will help you understand the new data you have collected. Comparing existing data to new data can highlight a cultural shift in the community or offer connecting evidence to support the new insights.

How to diagnose the situation

There are four steps to diagnosing the situation:

- Organize the research findings in a way that makes them easy to digest and to ensure that nothing is overlooked.

- Identify themes and trends that emerge from the data.

- Develop detailed insights that emerge from these themes.

- Create problem and opportunity statements to prioritize challenges and leverage points.

Organize the research | Identify themes | Develop insights | Create Statement |

Make sure to include everything you’ve collected

| Get to know the data

| Forming a deep understanding of the situation

| Articulating the contextual challenges and opportunities

|

Getting started

Gather every piece of raw evidence collected during the research phase. This includes documents with statistical results, observational notes, recordings and transcripts from interviews and focus groups, as well as notes and photographs (perhaps even video) from observations. Everything is useful. For example, if interviews were conducted with education professionals in a school environment, then any leaflets picked up from the location or photographs of the environment will help bring the research to life. It’s important to be comprehensive at this stage, so that no data or connections are overlooked. Data and information from the desk review must also be included at this stage.

A little trick Before jumping into the three following phases, it can prove very helpful to play a little memory game particularly if the research involves qualitative methodologies (interviews, focus groups, or observations). While you do have notes and recordings of these sessions, your memory can provide valuable insight. Your memory will be most useful immediately after the research phase. Draw on your own expertise, experience and perspective to pinpoint particular moments.

Ask yourself: What is most memorable to me from the session? What stands out? What do I want to know more about? What did I notice in the environment that wasn’t spoken about? |

1. Organize Research

Organizing data makes it easier to digest and ensure that all insights hidden within the research are surfaced. Without organizing the data, we may become reliant on our assumptions for answers or focus on the most obvious insights. It is essential to come to the diagnosis phase with fresh eyes and a belief that you do not yet know all of the answers.

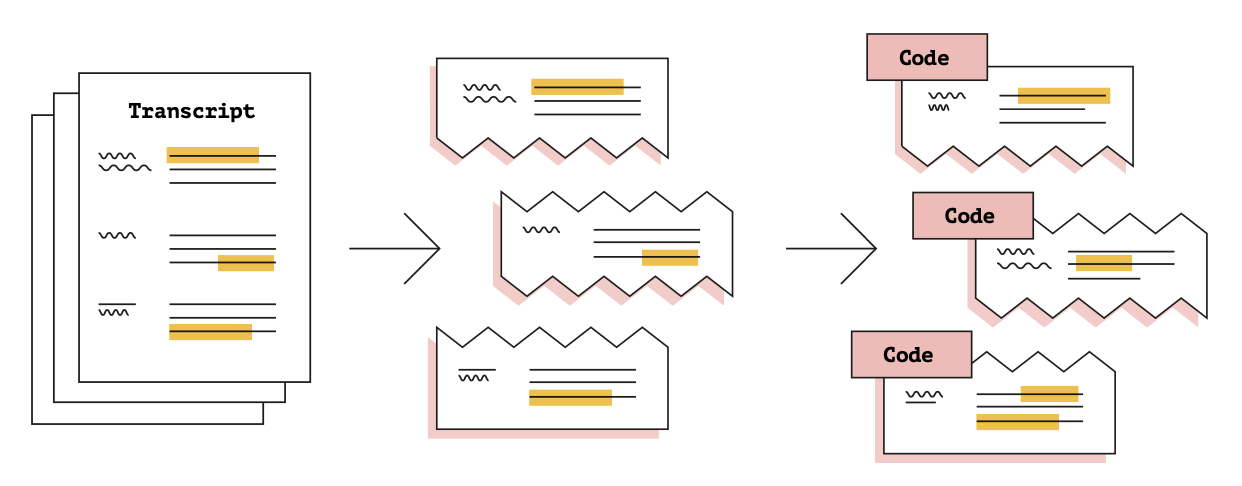

Coding

Coding data is about highlighting key pieces of information and organizing them into subjects. For example, multiple people may have commented on waiting time when seeking health services, or family pressure to conform to certain practices.

These comments could be codified under ‘access difficulties’ or ‘familial influence.’

- Get more than one person to read each transcript and coordinate on code creation

- Add highlighted data verbatim into the first column

- Lay out the codes in the following columns

- Mark where the data correlates to the codes

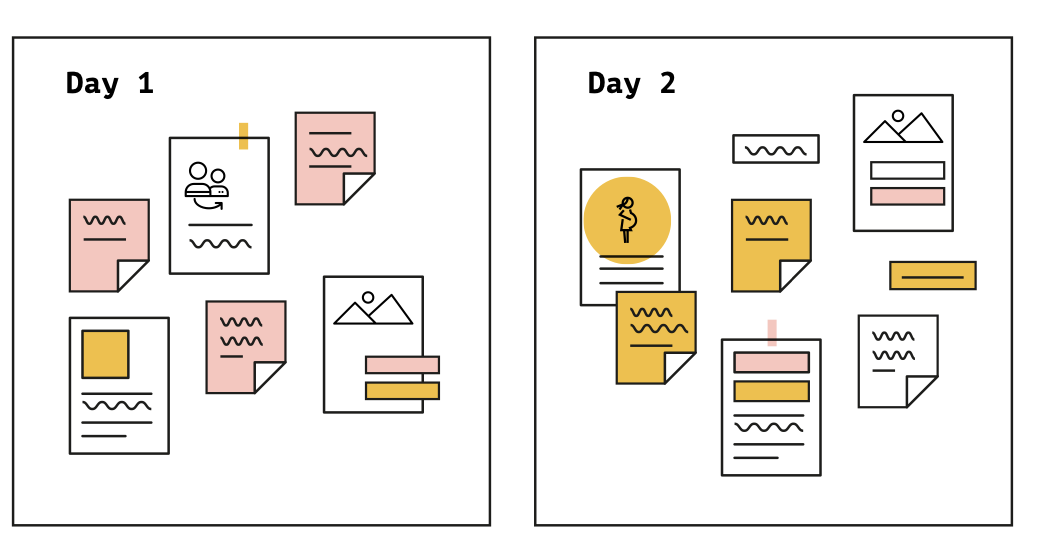

Research wall

Research walls - posting research onto a wall and group it according to themes - can spark insights by providing visual stimulation and the ability to look across multiple research assets simultaneously. The wall can also be used to document any insights elicited during thematic development.

This works especially well with qualitative data, but is also useful for quantitative data. Possible materials to post on the research wall include photographs, interview quotes, sticky notes with observations and other miscellaneous materials collected from the field.

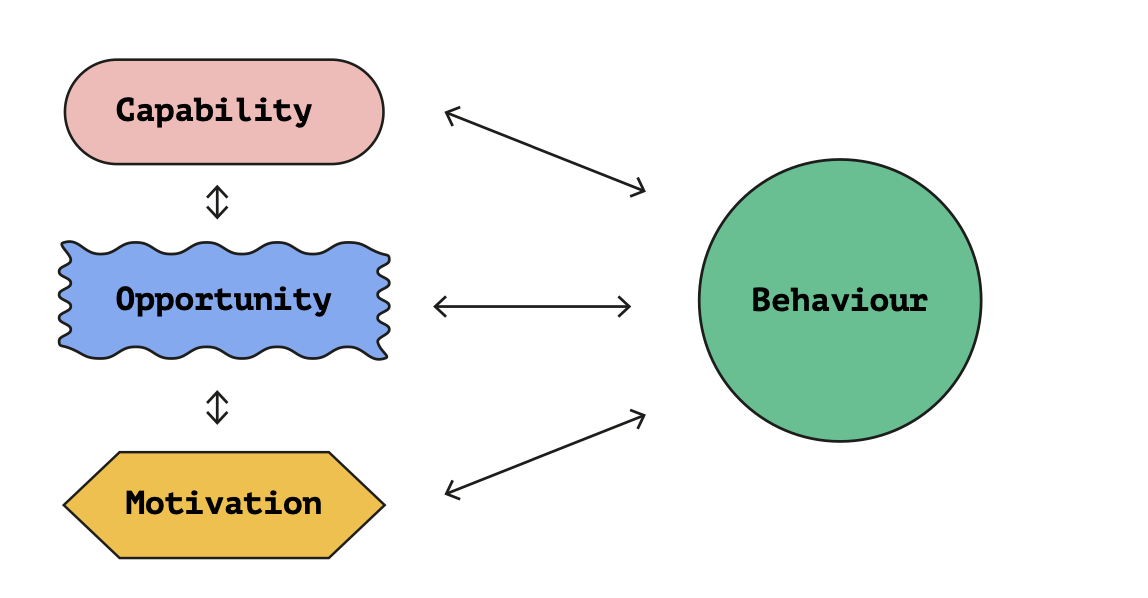

Mapping

Existing models and frameworks can be useful to map data against. Models provide a structure that takes into account the different contextual layers involved in a social or behavioural change process. Mapping to a model can highlight key areas or moments where the barriers or opportunities are prevalent.

Consider the following models:

- The COM-B Model

- The Socio-Ecological Model (SEM)

- The Behavioural Drivers Model

- Diffusion of Innovations Theory

- Social Network Theory

Management tip: Vocalize any preferred models early on in the process, so that it can guide the design of the research.

2. Identify themes

Once the evidence has been organized, you can move on to thematic analysis and development. What observations and visualizations connect to highlight a barrier or a strength within the community? You can use the codified data to spot trends and recurring themes. Codes help you build an in-depth understanding of the situation.

Make connections

- Allow time for individual review, and determine themes of interest. These themes can be documented through notes and sketches or turned into a verbal narrative.

- Come together as a team and share individual observations. How do others in the team respond? Does everyone agree that themes are relevant and substantiated? This is an opportunity to combat biases, so expect some disagreement and debate.

- Cross-reference your themes with existing knowledge from the desk review. Does the research provide a new understanding of the context or correlate with some existing assumptions? Look for supporting evidence in existing data.

Don’t neglect outliers

- While recurring themes will provide the bulk of the insights, it is wise to consider outlying statements and data points in the research. Ask questions about the outliers: Do any of them catch your eye? Why did this person say something so different to everyone else?

- Discuss these observations with your diagnosis team. Outliers are often valuable, particularly in regard to social norms. How and why have outliers broken norms? What has enabled them to do so? Is the behaviour sustained? What has been the result? Viable, existing local solutions can often be hidden in outliers.

Management tip: Do not pass up any valuable pieces of data. Ask the research team to share outliers to see if they can be developed into insights.

3. Develop insights

At this point, themes that can be turned into significant social and behavioural insights should begin to emerge. Use these themes to develop an even deeper understanding of the context and establish a narrative that can be shared with people outside of the research team.

Triangulate findings

It is important to substantiate each insight, even if it is not what the diagnosis team was expecting to find in the first place.

- Are there smaller themes that need to be triangulated? Look for supporting evidence in the desk review and existing literature. If further evidence is not found, it might be worth carrying out more research to fully understand the theme.

- Significant themes in the research should be investigated further. Can this finding be understood more deeply? Has a recent event caused a certain social norm to deepen or shift?

Management tip: Provide the contracted research team with your organization’s relevant collective intelligence at the beginning of the research. Do not assume that everyone understands the context as well as you do. It is important to share any internal research or documents that can support the research team in their process.

Find the story

Once the findings of the research have been substantiated and quantified, you can turn them into a story. By doing so, your findings can be easily communicated to people not involved in the research – communication specialists, designers, government officials, community members and decision-makers who need to sign off on any action. Insights are all about communicating research findings in a way that can be easily understood. This is especially important when sharing insights with affected communities.

- Think about assets created throughout the diagnosis phase. These could be sketches, significant quotes pulled from the research, sound bites from interview recordings, graphs, behavioural models with mapped findings or powerful photographs. These are all tools that can be used in combination to communicate and evidence the insights.

- Think about the audience that needs to understand the diagnosis. What type of evidence will they find most convincing? Be careful not to fabricate beyond the insight at this stage. Remain true to the data and community being represented.

4. Create problem and opportunity statements

At this point the research has been fully distilled into key insights. To move into the solution phase, it is important to prioritize your findings and focus on priority challenges and key opportunities.

Prioritize insights

When prioritizing insights you should consider:

- When bottlenecks occur: For example, when both supply and demand issues are present, supply should be addressed first. If demand improves but supply remains inadequate, it could lead to a very negative user experience and increase or create barriers.

- The scale and influence of bottlenecks: Does anyone insight present such a significant barrier to change that it must be addressed first? Consider social norms. It is unlikely that people will adopt a new behaviour that creates friction within their social environment, no matter how supportive the structural environment becomes.

- Existing resources: What local means are available to support change? What local experience or value seems the most promising or inspiring? What do community members rely on? What or whom do they trust?

- Actions with the most immediate impact: For example, if vaccine supply is low in the context of a pandemic, it may be beneficial to prioritize actions like distancing and hygiene before focusing on vaccine demand.

Crafting statements

The final step to diagnosing the situation is summarizing the prioritized insight in a couple of statements. These can act as guides during the solution phase, and can be referred to at different moments to make sure that the programme remains rooted in the local context. A good statement frames the challenge or opportunity from the perspective of someone within the community, or at least acknowledges how they are directly affected.

Statements should include:

- The context

- The people affected or the asset offering a solution

- The change we would like to see (social or behavioural)

- What is impeding and what could facilitate this change

In ___place__ , the ___people____ find ___behaviour___ difficult to complete because __reason__.

In ___place__ , the ___people____ face ___social issue___ because __reason__.

In ___place__ , the ___asset____ could help overcome ___issue___ because __reason__.

Examples

Below are some hypothetical examples that are NOT based on research.

In Scotland, young people find reducing their alcohol consumption difficult because there are few places to socialize other than bars and pubs, and they don’t want to be excluded from their group of friends.

In Zambia, healthcare workers find maintaining motivation difficult because they work in understaffed teams, don’t see the value of good performance and don’t see benefits or sanctions applied.

In Egypt, framing community engagement around the value of the family could help overcome harmful practices against girls, because the respectability of the family unit matters more than the individual child affected.

Management tip: Members of your research team may have their own process for defining problems and opportunities. Agree on a process early on to clarify expectations and eliminate any confusion around research deliverables. Listen to your research team. They may have a creative way to communicate their diagnosis that will work well for you.

Create - Diagnosing the Situation

Download this article as a PDF

You can download the entire page as a PDF here